elisa ohtake

macbeth

opera

nominated for the APCA award for best opera 2025

MACBETH OPERA

by Giuseppe Verdi

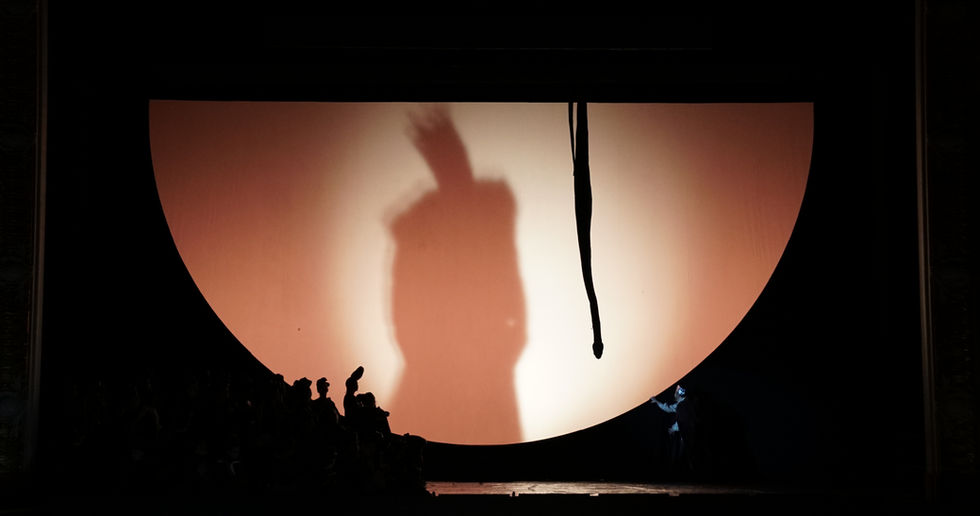

“Macbeth Opera” plunges into the dark sublime of tragedy, following Macbeth and Lady Macbeth in their vertiginous descent into chaos, driven by desire, hubris, and the shadows of the unconscious. The staging explores dark vortices, echoes of the “golden circle”—a symbol of the crown revealed only at the end—and elements of excess that cut across bodies, space, and objects. Drawing on contemporary theatre, images of ultraviolence, and structures that seem to collapse alongside the characters, the production confronts our torpor in the face of a world saturated by war and sensory overload. A visceral encounter between Verdi, Shakespeare, and the present moment.

Opera Libretto Text:

ABYSS AND TORPOR

Macbeth / Shakespeare / Verdi and the abyss of life.

Macbeth and Lady Macbeth instigate—and plunge into—their own chaos. They move from the highest to the lowest, from the best to the worst. The witches reveal what lies in Macbeth’s deep unconscious, entangling him in his own desire. But the project of tyranny is lost in a spiral of madness, in assaults of conscience and dark whirlwinds.

I usually conceive set design and stage direction together; it is difficult for me to think of one without the other. For this opera, I undertook an investigation of the dark sublime in Macbeth: the “golden circle,” a symbol of the crown in Shakespeare’s text, is explored here through its infinite shadows, visual echoes, and dark vortices in space. The golden circle itself appears only at the very end of the staging.

I also bring a measure of my freedom from contemporary theatre to explore unfoldings of excess, of hybris, already present in Shakespeare and Verdi. Just as the protagonists’ violent greed operates in excess, so too do certain stage objects and their handling. Lady Macbeth not only cannot wash the blood from her hands—she spreads it across walls and furniture; not only does the opera’s narrative oppress the characters, but the very structures of the castle do as well—walls and ceiling, including the sky above—until the latter collapses, evoking David Kopenawa.

With the speed of screens, we are living through an overlap of wars unprecedented in history, and we remain anesthetized. In the context of opera, however—with codes far more fixed than those of contemporary theatre—even small extravagances tend to be more noticeable, and potent estrangements can be amplified, including those surrounding ultraviolence and our present torpor.

Last year, I received—with surprised joy—an invitation from the director of the Theatro Municipal, Andrea Caruso Saturnino. I accept it again now with a different kind of joy: more complex, more alive and more dead, emerging directly from the lights and shadows of Verdi / Shakespeare / Macbeth.

Elisa Ohtake

October / 2025

Macbeth Opera

by Giuseppe Verdi

São Paulo Municipal Theatre

Stage Direction and Set Design: Elisa Ohtake

Musical Direction: Roberto Minczuk

Libretto: Francesco Maria Piave

Lighting Design: Aline Santini

Costume Design: Gustavo Silvestre and Sônia Gomes

Movement Direction: Roberto Alencar and Elisa Ohtake

Assistant Director: Ronaldo Zero

Assistant Set Designer: Carol Bucek

With the Municipal Lyric Choir and the Municipal Symphony Orchestra

Marigona Qerkezi and Olga Maslova: Lady Macbeth

Craig Colclough and Douglas Hahn: Macbeth

Savio Sperandio and Andrey Mira: Banquo

Giovanni Tristacci and Enrique Bravo: Macduff

Mar Oliveira: Malcolm

Julian Lisnichuk: Assassin, Messenger, Servant

Isabella Luchi: Lady-in-waiting

Rogério Nunes: Doctor

reviews

MACBETH IN A PAULISTA KEY

Opera as a class form — and a mirror of São Paulo

Methodological note. My field of practice and writing is theatre. To write this review, I undertook specific research on opera—its history, conventions, and critical debates—in order to situate the production within its own field.

A review of this staging demands more than a description of singing or scenography. It requires unveiling the historical and social forces that opera, as a form, carries within it. Elisa Ohtake does not propose a spectacle about the past; she places the operatic tradition at the service of a diagnosis of the present.

Everything begins with Verdi’s score—not as background, but as a political decision materialized in sound.

Verdi “socialized” Shakespeare’s three sisters. Where the playwright offers a whispering, elliptical trio, the composer creates a collective female chorus: sonic power, ugly, cutting, repulsive. In his letters, Verdi was explicit—no decorative witchcraft. The music is made of cuts and edges: staccatos, angular rhythms, insect-like repetitions, diminished chords, chromaticism, piercing woodwinds, percussion that scratches. In the cauldron of Act III, fate is not lyrical; it is sonic aggression.

Ohtake reads this with precision. She uses thirty-six female voices—twelve from each section—not as ornament, but as the full realization of what Verdi already inscribed: the witches as a collective organism that embodies the ideology of ambition. They do not comment on the drama; they propel it. The roughness multiplies thirty-sixfold. They appear as a female wall, each with distinct costume and posture, preserving individuality within the mass—the effect is that of a scenic-musical machine driving Macbeth toward the abyss.

The difference between Shakespeare and Verdi is the difference between the individual and the social. Shakespeare offers the enigma of the Weird. Verdi transforms it into toxic common sense—the voice of the streets that naturalizes plunder, calculation, greed. In Ohtake’s reading, this chorus is São Paulo: invisible yet omnipresent—algorithms optimizing profit, whispers that legitimize violence, mass psychology wielded by the power of chorus.

If the witches structure chaos, Lady Macbeth is the individual who denies it—until she is consumed by it.

The video projections do not show abstract delirium. They show her walking, thinking, criticizing—objectively. Duplicated on screen, she narrates her actions and already critiques herself. She does not live power; she exposes it while exercising it.

This is Brecht, but not dogmatic—Brecht translated into operatic language. Verdi demands total, overwhelming presence: the music makes affect an undeniable inner truth. The operatic voice does not lie. Ohtake does not negate it; she uses it. The projection doubles the singing and exposes its contradiction. Lady Macbeth sings guilt while we see her thinking it. The distance between song and thought is where critique resides.

The second operation is the city as living scenography.

There is no Birnam Castle. There is São Paulo—not as illustration, but as the material structure of the drama. Projections show the metropolis where private ambition is realized, where violence circulates as capitalist logic. The Brechtian distancing shouts: “This is not eleventh-century Scotland; this is here and now.” Visible inequality, rational paranoia, ambition as weapon—São Paulo is not scenery; it is a character. The witches are the city speaking. Lady Macbeth is the elite that imagines it can dominate it. Macbeth is anyone who believes in ascent because the city promises it every day.

The singers do not “suffer” the drama—it is imposed on them as structure. Verdi’s music is irrevocable. But the mise-en-scène rejects realism: ritualistic, symbolic, constructed. The singer does not hide within emotion; they are exposed by artificiality. A fine dialectic: affect is real, but constructed, social, ideological. The spectator is held in tension between music and critique.

Ohtake overcomes the false dichotomy between “culinary opera” and pamphlet. She uses the totalizing force of the form—the chorus multiplied by thirty-six, the opera’s single vocal mass—to create allegory without consolation, only unsettling clarity.

The witches are not supernatural fate; they are the collective logic that whispers ambition.

Lady Macbeth is not an isolated queen; she is the bourgeois subject who discovers, too late, that violence returns as guilt impossible to wash away.

Macbeth is anyone who believes they can rise in a city that only knows how to descend.

At the end, there is no catharsis. Only the high-voltage question:

who are the witches whispering in our ears today—and how far will we go to crown our ambitions?

Márcio Boaro — for Os que lutam

https://osquelutam.com.br/2025/11/3302.html

LONG LIVE OPERA ALIVE!

In an abstract and cold staging, the new Macbeth at the Theatro Municipal delivers high-level musical performance; defenders of the “great operatic tradition” shout from the audience.

A modern staging, with striking lighting resources and a vast inclined silver platform, set the tone from the very first act of Macbeth, the new production at the Theatro Municipal of São Paulo, which premiered yesterday, October 31. In the program text, stage director Elisa Ohtake writes that she conducted an investigation into the “dark sublime in Macbeth—the ‘golden circle,’ symbol of the crown in Shakespeare’s text, is here explored through its infinite shadows, visual echoes, and dark vortices in space.”

Accordingly, large concentric circles or a sphere occupying the entire back of the stage, under contrasting lighting, recur throughout the performance. Other scenic elements evoke industrial contemporaneity, such as transparent inflatable plastic armchairs or detergent containers with which Lady Macbeth unsuccessfully attempts to rid herself of bloodstains. An artificial materiality predominates. In addition, a huge black plastic scorpion appears in some scenes, an allusion to death by one’s own venom. There is no life, no nature. What exists is ambition, power, and death.

Visually intriguing, the production conveys coldness through its scenic aridity and its dominance of luminous contrasts and shades of gray. The costumes are well designed and cohesive, yet also dark, in blacks and ochres. It is no coincidence that the yellow-light scene at the beginning of the fourth act—the exiles’ scene—was among the most moving, as were the scene with the golden circle and the forest that moves like a floral procession.

The minimalist and abstract approach somewhat compromised narrative clarity. Passages that in the original contain great dramatic potential—the witches’ prophecy in Act I, Macbeth’s hallucinations during the banquet, or the apparitions in Act III—lost emotional force. If the inclined platform has strong impact in the first and third acts, it seems to lose effect, perhaps through repetition, in the final act, where, with the projected image of a sky, it slowly suffocates Macbeth.

The cohesion might have held, were it not for the questionable decision to interrupt the opera midway through Act II for the projection of a “behind-the-scenes” video. We see the Lady Macbeth protagonist explaining that we must wait for the set change and leading us to her dressing room, where she reads a passage from Shakespeare not included in the opera. Shortly after, another video shows Macbeth on the exterior steps of the Municipal buying popcorn from a street vendor—all with a handheld, “live-camera” aesthetic, improvised movements and informal close-ups.

The videos became the pretext for self-appointed defenders of the “great operatic tradition” to shout from the audience. Loud cries of “shame!”, “out!”, and other coarse expressions produced a lamentable moment of radicalization and intolerance. In response, applause erupted, along with cries of “silence” and “respect”—and, equally, a few less polite expressions.

It is a pity that these defenders of “great operatic tradition,” in their rage-altered state and with hearts pounding at their temples, likely missed the best of the evening: the spectacular musical performance.

First and foremost, a cast of vocal soloists at a very high level, led by the impressive performance of soprano Marigona Qerkezi. Born in Kosovo and raised in Croatia, Qerkezi delivered Lady Macbeth with a brilliant, powerful voice and great musical empathy. The American bass-baritone Craig Colclough also gave a strong portrayal of the tortuous Macbeth, with rich timbral nuance. Another highlight was Banquo in Savio Sperandio’s excellent performance—long admired for the beauty and intensity of his voice, as well as for his intelligence and interpretive taste. Tenor Giovanni Tristacci was also strong as Macduff, as were Mar Oliveira as Malcolm and Isabella Luchi as the Lady-in-waiting.

Under conductor Roberto Minczuk, the Municipal Symphony Orchestra once again demonstrated its excellent operatic form, displaying balance, a beautiful sound, and great theatrical drive. The Municipal Lyric Choir lacked some sonic consistency and precision, though not to the point of compromising the overall result.

All things considered, Macbeth is yet another high-level initiative by the Theatro Municipal of São Paulo, which with each new production grows more crowded and resonates more strongly within the city’s culture. While over the season as a whole I miss the presence of more directors specialized in the genre—not by chance the pairing Le Villi and Friedenstag directed by André Heller-Lopes stands out as the year’s lyrical highlight—it is impossible to deny the vitality and cultural force emanating from Praça Ramos de Azevedo.

Aesthetic disagreements and interpretive divergences are the soul of a vibrant, participatory theatre. Long live opera alive!

Nelson Rubens Kunze